Before we were handed over the keys to our newly rented Berlin apartment, the previous tenant casually dropped a sentence that immediately sparked my curiosity: „Someone notable once lived here.“ He wasn’t quite sure who exactly it was, but the hints he provided were sufficient for a literary scholar to start his research. The evidence left no doubt that the predecessing resident was Walter Benjamin, the thinker, cultural historian, and writer born in Berlin in 1892 who died 48 years later in exile by his own hand.

In a letter to his friend Florens Christian Rang, Benjamin wrote on November 18th, 1923:

“I have had a small room here (...) at Ruben's Garden House III for some time now. My work has been progressing better since I have been enjoying an almost extraordinary peace and quiet.“

During his brief lifetime, Benjamin moved a lot between European cities (Paris being essential for his work) and within his hometown, Berlin. His residence in our street lasted just four months, from November 1923 to February 1924. However, the productivity he reported to his friend included preparatory work for his book „The Origin of German Tragic Drama“ and the earliest and longest text for his collection of short prose titled „One Way Street.“ Both books were published in 1928.1

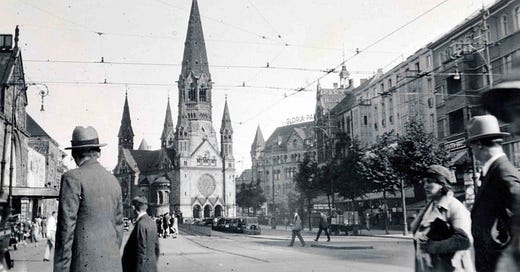

Modernity’s birthplace, 100 years later

Benjamin wasn’t the only notable person who lived in our new neighborhood. In fact, it has been called a birthplace of literary and cultural modernity. Writers who resided within walking distance include Bertolt Brecht, Erich Kästner, Heinrich Mann, Robert Musil, and Kurt Tucholsky, to name just a few.

It’s one thing, however, to stroll through the streets tracing cultural history and another – being a writer yourself – to learn that a giant most likely put his hand on the same staircase railing you touch day in day out. While there is no evidence that Benjamin has actually written anything in my study, he somehow is my roommate now, which is quite ambivalent a fact to deal with.2

Of course, any comparison is ridiculous; any talk of an inspiring genius loci feels contrived, just as any complaint about what the late Harold Bloom called the „anxiety of influence“ feels trite. Honestly, I was inclined not to write this piece at all, not knowing how to avoid basking in the light of that larger-than-life figure who happened to spend some time close to my desk a hundred years ago. Two insights, though, changed my mind:

Benjamin wrote, „My work has been progressing better since I have been enjoying an almost extraordinary peace and quiet.“ This sentence reminds us that writers are real people in real places, trying to progress under real-life circumstances. The Benjamin revered worldwide today is not the thirty-one-year-old man in a rented apartment desperately seeking some calm in his messy life.

„One Way Street,“ the book Benjamin partly wrote in the quiet garden house that now has high-speed internet access, is so intriguingly connected to what writers try to accomplish a century later that it makes perfect sense to think of Walter Benjamin as an imaginary roommate of all contemporary writers trying to capture their own times and experimenting with new formats in the digital realm.

The invention of freeform

„One Way Street“ is a collection of sixty short prose pieces with a particular interest in everyday things and practices, titled, for example, „Haberdashery,“ „Office supplies,“ or „Interior design“. Many of them first appeared in papers and magazines. Benjamin, who collected objects of popular culture such as postcards and children’s toys, wanted to unlock the signature of his time in the seemingly banal, mixing art criticism, political commentary, and formal innovation.

Together with authors like Ernst Bloch, Siegfried Kracauer, and Joseph Roth, Benjamin’s literary-cultural miniatures have pioneered a way of experimental writing that has been named “Kleine Form” („small form“) by the critic Alfred Polgar in 1926. The basic idea was that only highly current, episodic writing is suited to capture the dynamics of modernity. This text type, the Austrian writer Hugo von Hofmannsthal wrote already in 1907, effortlessly moves „from street scene to an unsolvable mystery.“

Is it too far-fetched to compare the new writing style invented a century ago and the creative freeform the best independent writers on the web display today? There are striking similarities as well as significant differences between the two:

Just like the Kleine Form originated with the flourishing of a new medium – the printed newspaper and its cultural section called Feuilleton – blog posts, email newsletters, and shortform-formats with their quick back-and-forth presuppose the emergence of a new technology, namely the world wide web.

Feuilleton and digital writing share a similar temporality that differs from a book’s deep dives. Even though some writers cultivate long-form texts and a slower cadence online, most digital writing is daily or weekly: worldly, fast, and agile.

Many writers of the 1920s, including Benjamin, were politically inconvenient and heterodox, resisting the rise of totalitarianism in Europe. While the ideological landscape is different today, many writers avoiding the gatekeepers of mainstream media share a spirit of independent thinking with their predecessors.

Of course, there are differences, too:

With English being the lingua franca of globalization, it’s hard for a writer from a non-English speaking country to be part of the conversation on, say, Substack without writing in a second language.

While the discourse of the 1920s Feuilleton was very much sparked by philosophy and art, many of today’s inspiring thinkers are more science-based in their approach.

The last point, however, brings me back to one of the most remarkable similarities: language. Think, for example, of Gurwinder Bhogal’s tremendously successful Substack The Prism. His writings on „meta-knowledge“ aim to be data-driven and evidence-based, yet his language is varied and playful. The lists of numbered „truths“ he publishes contrast nicely with the spirit of falsifiability that his writings embrace. Particularly in more conversational formats, he scrutinizes serious topics while maintaining a sense of humor. Gurwinder takes concise positions but welcomes critique and is more than willing to correct himself. Hence, his attitude and the matching formats share many characteristics with Feuilleton-writers of early 20th-century modernity.

A sense of ancestry

Web writing tends to be quite ahistorical, not remembering those who cultivated similar sentiments in pre-digital times. While it sometimes makes sense to reinvent things from scratch, it’s undoubtedly beneficial to keep in mind the rich tradition web writers consciously or unconsciously draw from. Here’s a list of short-form writing that made a lasting impression on me in various stages of my reading life:

the poetic fragments the German writers Friedrich Schlegel and Novalis invented in Early Romanticism

the loosely arranged reflections of philosophers such as Friedrich Nietzsche, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and Theodor W. Adorno

many writings from 20th century France, including the intellectual notebooks called Cahiers written every morning of his adult life by poet Paul Valéry, the playful post-war literature by a gathering of primarily Parisian writers called Oulipo, and the fragmented cultural critique by master semiotician Roland Barthes

the hardly decipherable so-called "micrograms" the Swiss writer Robert Walser jotted down using a minuscule pencil

the almost forgotten „One Minute Stories“ by the Hungarian writer István Örkény

If you’re a writer in the digital realm, check them out for inspiration. If not, read them anyway. And, of course, don’t forget Walter Benjamin, who I am thinking of right now while typing the last sentence of this article in the very same garden house where this restless, tragically unfinished pioneer enjoyed some peace, at least for a couple of months.

Even though the Roman numeral in his letter very likely indicates the floor, it’s important to note that there are two separate apartments on this floor, so maybe it was our neighbor’s apartment where Benjamin spent some time.