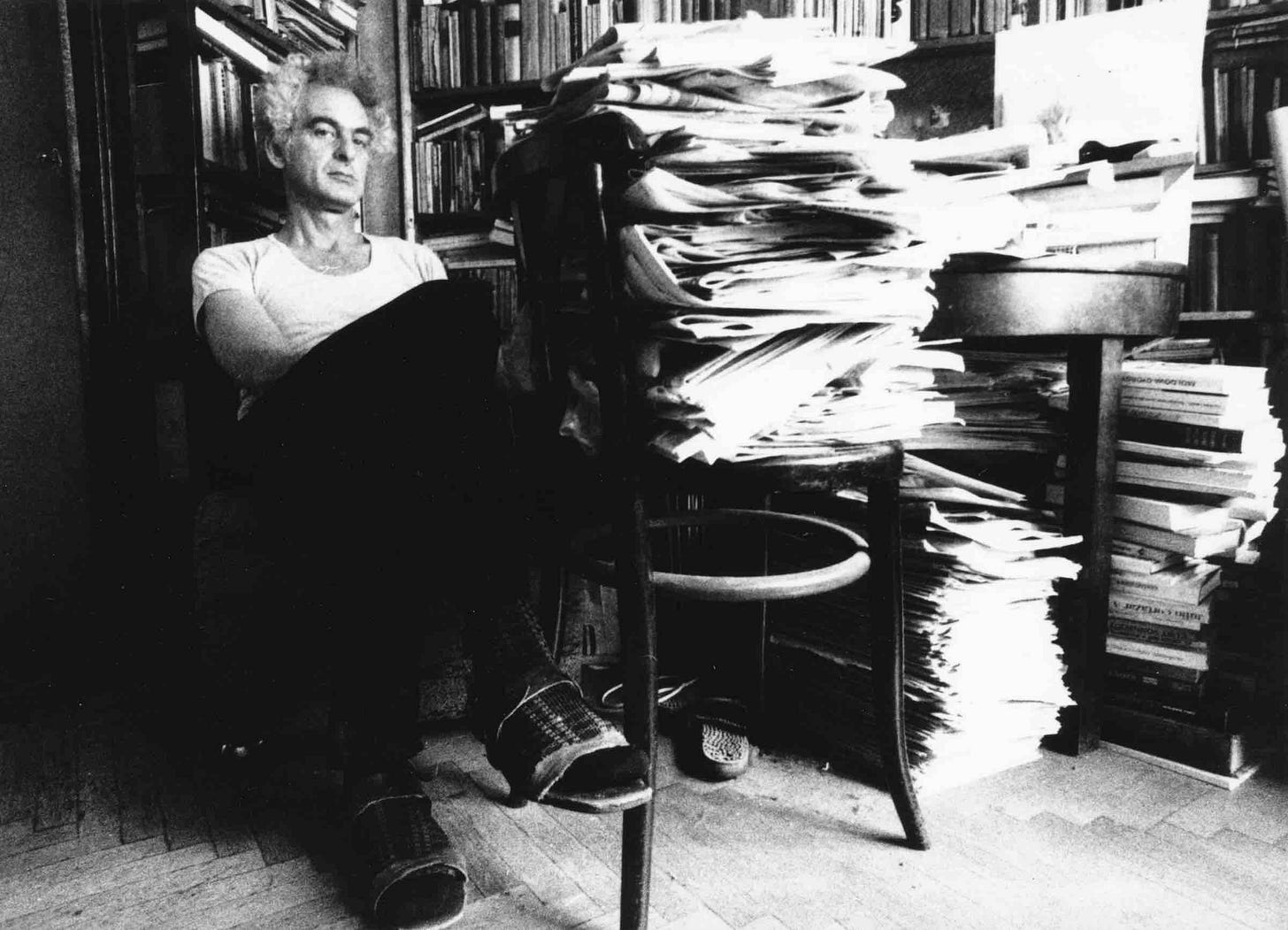

The beginnings of my engagement with culture and the world of ideas date back to the Gutenberg galaxy. I read printed newspapers, from which I cut out and saved articles. I made photocopies of scientific essays in libraries, which I filed in folders. I bought printed books, in which I left underlining and annotations in pencil. The piles of materials grew, the number of folders increased, and the shelves were no longer sufficient to line up books in a single row. Every move – an effort. Every addition – a puzzle of allocation. Every text I wrote – a compulsion to work through the piles of paper again.

The first turning point: from print to digital

While I was still ruminating about the best way to deal with my miniature edition of the Library of Babel, personal computers and the internet came along. Relieved of the weight of printed matter, the organization problem presented itself anew: Which arrangement of text documents, PDFs, scans, read-later lists, and bookmarks is best? How should I name the documents and tag the folders? What can you do when an outdated file can no longer be opened? There were an awful lot of problems, but they all paled behind the sheer infinity of information available with a click of the mouse. Was it even a sensible undertaking to strive for a personal order of materials?

The second turning point: AI

One day, I realized that full-text search on my Mac had become so good that it was best to simply search all documents on the hard drive or in the cloud for keywords. Sorting the files in advance became unnecessary. Recently, AI chatbots have become even more efficient in getting the information needed. Just ask or enter a dialogue, and the LLM will provide increasingly accurate and well-structured answers, including summaries and citations. So why collect material in the first place?

I realized it was finally time to reorganize my information system. But how? What could information management look like that doesn't unnecessarily complicate things without abandoning those elements that are the prerequisite for independent thinking and writing?

Handling information in the age of AI – three ideas

I'm just starting to set up an information system that is up to date with technological developments. Here are my first thoughts:

Finding material: add serendipity to the mix

The more polished LLMs become and the better they understand individual users' contexts, the more important it will be to feed serendipitous findings into one's information diet. This could include interesting text from other disciplines or positions outside one's opinion bubble.

The models are only as good as what was put into them. A randomized change of perspective can inspire and irritate productively. It clarifies that many things are complicated, nuanced, and ambivalent. It brings the unease of contingency and blind spots into play.

Recombining material: provide friction where it’s useful

Knowledge and text production is not just about information, computation, and automation but also about evaluating sources, understanding contexts, and practicing judgment. AI is superior at aggregating massive amounts of data. Therefore, using LLMs as assistants to gather knowledge for particular projects saves detours and time by quickly searching, summarizing, and citing huge inventories. However, when it comes to shedding new light on something in the world, the manual collection and sorting of material can be a meaningful part of the creative process. Likewise, slowly reading a challenging book and taking notes differs from retrieving a summary. Mental friction can deepen understanding, solidify memory, and spark new ideas.

Shaping material: trust your brain

In my essay about my desk, I wrote:

„At the end of the day, writing is about gaining clarity: choosing what is relevant, sharpening ideas, and finding the best structure to convey what is essential. The best tool for that still is one's head.“

Anyone who wants to produce original thoughts and idiosyncratic artifacts is well advised to absorb a lot of information but then follow their instinct, intuition, and gut feeling. Productive forgetting will ensure that the relevant elements sink in and return: ideas stick, patterns surface and frameworks emerge.

AI knows more than you; only you know when the outcome sings.